Foreword

Arbitrage is the bedrock of almost all modern financial transactions. Arbitrage is what keeps ETFs and their underlying trading somewhat in sync, it is what prevents futures from drifting from their underlying, and it is what options pricing (Black Scholes model and its modern derivatives) is ultimately based on.

As usual, a reminder that I am not a financial professional by training — I am a software engineer by training, and by trade. The following is based on my personal understanding, which is gained through self-study and working in finance for a few years.

If you find anything that you feel is incorrect, please feel free to leave a comment, and discuss your thoughts.

Volatile volatility

For those who are not aware, VXX is a ETN which is benchmarked against the VIX. There is a formula which ties the price of the VXX to the underlying VIX futures. The fund is backed by a well funded provider, so in theory, VXX should trade fairly closely to the VIX during regular trading hours.

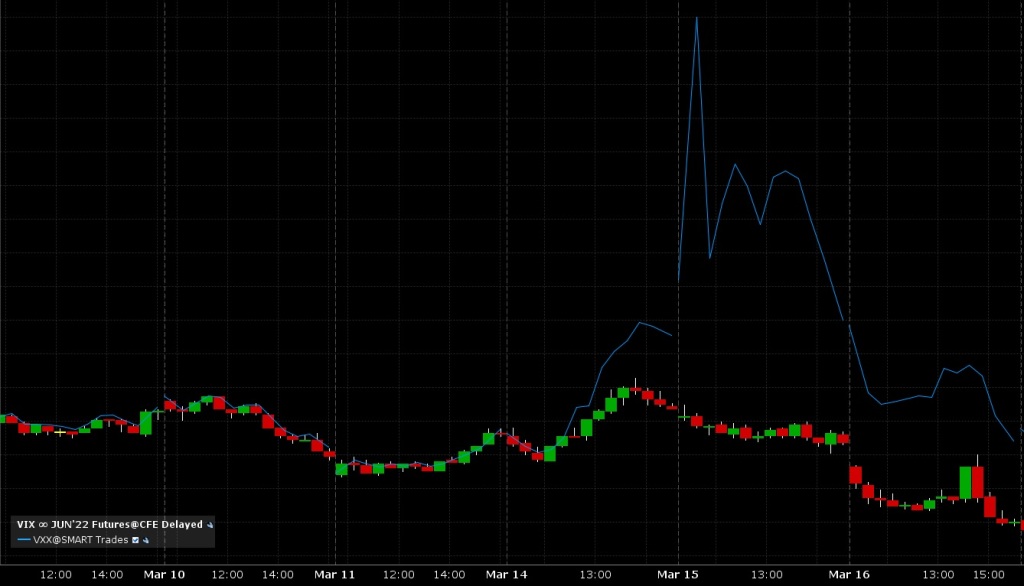

If you look at the graph below, charting VIX (the candlesticks) vs VXX (the blue line), from March 9, 2022 to March 16, 2022, you’ll see that VXX and VIX move more or less in sync… until March 14. On March 15, VXX just went berserk.

What happened?!

ETNs, like ETFs, are kept in sync with their benchmarks mostly by market makers (more accurately, a subset of market makers called authorized participants). The details of how this works doesn’t matter, except that it relies on arbitrage:

If the ETN is trading higher than its benchmark, the authorized participants (APs) can short the ETN on the open market, and then buy newly created shares from the ETN provider at the price indicated by the benchmark to cover their short. Because the APs are selling (shorting) at a higher price than what they are paying the provider to create new shares to cover their short, the APs make an arbitrage profit — a “riskless” profit (1). Since it’s “riskless” profit and thus “free” (1) money, the APs will happily do this all day as long as the ETN is trading above the benchmark. The act of the APs constantly shorting the ETN will eventually cause the price of the ETNs to drop, so that it matches the benchmark.

If the ETN is trading below its benchmark, then the opposite happens. The APs will buy the ETN on the open market, and sell them to the provider at the higher price indicated by the benchmark. Again, the APs are making a “riskless” profit by buying low and selling high, so they’ll happily do this until their buying pressure forces the price of the ETN to match the benchmark.

So why didn’t the APs do anything on March 14 onwards?

On March 14, Barclays, the owner of the iPath funds (i.e. the provider) issued this press release: https://ipathetn.barclays/cms/static/files/ipath/press/Press%20Release_03_14.pdf

Essentially, Barclays is suspending the creation/redemption process mentioned above, where APs can buy/sell shares from it at the benchmark price. Effectively immediately, APs can still buy/sell on the open market, but they can no longer close their position via the 2nd leg of the trade, by selling/buying from the provider. This breaks the arbitrage chain, and there is no longer an arbitrage. No arbitrage, no “riskless” profit, and thus the APs stop their activities and the price of VXX goes haywire.

Arbitrage

The official definition of an arbitrage is a trade with 2 or more leg which:

- Results in the final positions being exactly the same as before all the trades.

- Results in a profit, despite the positions being exactly the same.

When all legs of the trade can be done simultaneously, then the arbitrage is said to be riskless. In the case of the VIX/VXX trade above, the legs cannot be done simultaneously since they are with different participants, so there is a small, but very real, time lag between each leg. Therefore, while it’s generally very safe, it’s not entirely riskless.

Notice the first crucial criteria — after all legs are completed, your positions must be exactly the same as before the first leg was made. This implies convertibility — at some stage, you must be able to convert whatever you have to something else to close a prior short or long. In the case of the VIX/VXX trade, the APs were able to convert cash from shorting VXX into new VXX shares by buying from the provider, or they could convert VXX shares into cash by selling to the provider.

But once convertibility is removed, there is no longer an arbitrage to be made.

As shown by the VIX/VXX trade, and GOOG/GOOGL in Q2 2021, whenever there is no arbitrage, there are zero guarantees that theoretical models of how things should trade would actually be realized.

There is no arbitrage without convertibility. (2)

Futures

Futures are essentially contracts signed between the buyer and seller (3) where they agree to trade some asset at some specified future time at some currently determined price. Details here.

Let’s say we enter into a futures contract, where I’ll sell you 1 barrel of crude oil 1 month from now. If the price of a barrel of crude oil on the spot market is currently $100, and the cost to store that barrel for 1 month is $2, then I’ll happily sell you that barrel in 1 month for any price $102 or more. I have an arbitrage — the futures contract provides the convertibility that closes the gap between “having a barrel of crude oil now” + “storing a barrel of crude oil for 1 month” and “selling a barrel of crude oil in 1 month”.

Similarly, for you, if you have a barrel of crude oil now, you can sell it for $100, and buy it back in 1 month for $102, while saving $2 of storage costs. Effectively, you have an arbitrage too, and so you’ll happily do this trade for anything $102 or less.

So the price to trade at is >= $102 (for me) and <= $102 (for you), and the intersection of those 2 inequalities is… $102. Because of the arbitrages on both sides, the futures contract will state that we will trade at $102 in 1 month.

In practice, of course, the math is a lot more complicated. The example above ignores the cost of money (i.e. interest rates), transport fees, etc. These fees (including storage costs) tend to be asymmetric so the trading price will be a range instead of a single point.

At the same time, if there is heavy speculation on one side or the other (maybe some really rich entity decides they really like a million barrels of oil in 1 month, regardless of the price), or other technical issues (all storage depots are completely full), then the futures price can temporarily be dislodged from the arbitraged range.

Very often (4), though, the futures markets are not predictive. In many cases (4), futures are arbitraged by producers and consumers of the underlying asset, so the stated trade price on the contract does not reflect any predictions on future spot prices.

Footnotes

- “Riskless” and “free” are in quotes because it’s technically not completely riskless — there are risks with regards to implementation (may be the authorized participant made a math mistake!), risks with regards to random events (maybe the market shuts down just after they short, but before they cover), etc. But with regards to the financial models of the assets, there are theoretically no risks.

- Implicit here, and shown by GOOG/GOOGL in Q2 2021, is that arbitrage is a critical component of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Therefore, if there is no convertibility, EMH tends to break down too.

- Technically, for stability reasons, both buyer and seller simultaneously sign contracts with the futures exchange. This way, the futures exchange is “hedged” (also a form of arbitrage!), but if either buyer or seller is unable to fulfil their requirements, the futures exchange will step in and prevent the contract from defaulting.

- I have been reliably informed that crude oil tends to be backwardation rather often, roughly half the time. During these times, futures prices are somewhat predictive of future spot prices. For more nuance, see the St Louis Fed’s take.