Foreword

Everyone in finance seems to be chasing alpha, but very few people seem to really understand what it is. What is alpha, and why does it matter?

As usual, a reminder that I am not a financial professional by training — I am a software engineer by training, and by trade. The following is based on my personal understanding, which is gained through self-study and working in finance for a few years.

If you find anything that you feel is incorrect, please feel free to leave a comment, and discuss your thoughts.

Simply alpha

Alpha, in finance, specifically quantitative finance, is defined as the excess returns of a strategy above and beyond market returns. In other words, alpha measures the outperformance of a strategy — the higher the alpha, the better the strategy1.

And because everything in finance is about *ahem* number measuring exercises, everyone in finance seems to be striving for higher alpha.

Unfortunately, many people, including those working in finance, don’t really understand what alpha is, and often conflate increased risk (which you do not want) with increased alpha (which you do want).

Maths

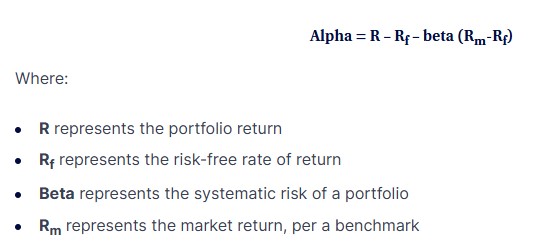

According to https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/career-map/sell-side/capital-markets/alpha/, the mathematical formula for alpha is:

If you look at the equation more carefully, you’ll realize that:

- Alpha is net of the risk free rate.

- Alpha is independent of market return.

Which is to say, if all the return of a strategy can be expressed as a function of market return, then that strategy, by definition, has zero alpha.

To “simplify” things a bit, to compute the alpha of a strategy, run a correlation test of that strategy’s returns against SPX minus the risk-free rate (assuming you are using SPX as a benchmark), and the correlation, with magnitude, is your beta. (edit: clarified that beta is correlation + magnitude)

The part of the strategy’s return beyond that which can be explained by market returns (i.e. beta(Rm – Rf)) would be alpha + Rf, so you can compute alpha by just taking away from that remainder the risk-free rate.

Some examples

Now, let’s consider some examples:

- A fund that simply buys SPY, returning 33% in 2021, -14% in 2022 and 19% in 2023, with a cumulative total return over the 3 years of 34%.

- A fund that simply buys UPRO (3x SPY), returning 106% in 2021, -49% in 2022 and 43% in 2023, with a cumulative total return over the 3 years of 50%.

- A fund that returned 6% in 2021, 8% in 2022 and 9% in 2023, with a cumulative total return over the 3 years of 25%.

Clearly, the second fund has the highest cumulative total return, but which strategy has higher alpha?

Well, SPY is basically just the ETF expression of SPX, and UPRO is just 3x SPY, so the correlation of both funds would be very close to 1 (with SPY having a beta of around 1, and UPRO having a beta of around 3, edit: clarified that beta is correlation + magnitude), which implies both funds have zero alpha. However, the 3rd fund clearly does not move with the market — it goes up every year even when the SPX went down in 2022, and if you do the maths, it is returning about 5% above the risk-free rate every year. So the alpha of the 3rd fund is actually 5%.

Cue surprise

The above result often surprises many who don’t really understand what alpha means — how can a fund that returns less than SPY be considered to have alpha, while a fund that returned almost double of SPY has 0 alpha?

Recall that alpha is the part of the return that is above and beyond what can be explained by market returns. Both SPY and UPRO explicitly try to mimic market returns, with the exception that UPRO does it with 3x leverage. So neither have an excess return above that which can be explained by market returns, and the additional return UPRO provides over SPY is really just the result of UPRO taking more risk, in the form of using leverage.

Recall when we said people often confuse more risk (bad!) with more alpha (good!)? There you go.

The 3rd fund, on the other hand, has 0 beta2, so all its returns are just alpha + Rf, and if you subtract the risk-free rate (generally assumed to be 10Y US Treasury yield), you get about 5% alpha per year.

But the returns suck!

Yes. Compared to both the first 2 funds, the return of the 3rd fund is indeed subpar. This is a common theme of true alpha funds — their returns tend to be around the 5-10% mark annually (edit: This is net of risk-free rate, i.e. alpha). Yes, there are some funds that have much higher alpha (e.g. the Medallion fund from Renaissance), but those tend to be closed off to outside investors.

The reason alpha funds tend to have lower returns, is because they are hard, and more often than not, they are rare. Alpha is hard because it is genuinely hard to find a strategy which will do well regardless of what the market does — most strategies have some non-trivial amount of beta associated with it just because they need to operate in the market. They are also rare, because most alpha strategies tend to have low capacity, meaning you can only put so much money into the strategy, before your positions affect the markets, and you distort the market enough that the returns dissipate.

Constructing an alpha only fund

To get some insights into a true alpha fund, consider a fund which returns 5% of alpha, and 80% of beta, i.e. the fund returns 80% of whatever SPX returns in any single year, and on top of that, returns 5% additionally (+ risk-free rate).

Well, we can convert such a fund into a true alpha fund by simply bundling this fund with a short up to 80% of your portfolio value of SPY. The total return of this bundle will now be: 5% + 80%SPY – 80%SPY = 5%, the alpha.

Not so fast though — shorting is not free. You typically pay a fee (short borrow fee, maybe margin costs, etc.) to short. To keep the maths simple, let’s say that the total fee for this shorting is 1% of total returns.

Which means, your true alpha fund, the bundle, will only return 4% alpha.

In general, a true alpha fund tends to involve a lot of trades to hedge out market exposure, which in turn will reduce the actual return (and thus alpha) of the fund.

Why bother?

So to recap, a true alpha fund first needs to find a good strategy, then pay fees to trade that strategy, and pay more fees to hedge out market exposure, just to get a net return of around 5-10% of alpha. While market return, at least in the past few years, has dramatically outperformed that with much less hassle.

So… why bother? Are Wall Streeters just stupid? Or maybe they just like Rube Goldberg-esque exercises in futility?

Let’s consider our 3rd fund again, which returned 5% alpha, i.e. 5% return net of risk-free rate.

Large institutional traders (and even savvy individual traders), can often get financing (i.e. loans) at, or close to, the risk-free rate.

If you are in such a position, then you can borrow, say $1m, at risk-free rate (Rf), then put that $1m into the fund to deliver a total return of alpha + Rf, which means effectively you get a return of alpha “for free”. Since this is a positive value arbitrage, you can simply re-lever your positions to get another loan at risk-free rate, put that new money into the fund to increase your returns. This process can be repeated forever — an infinite money glitch.

The ability to re-lever into positive alpha strategies, is also why these strategies tend to be rare — any existing alpha found will likely be pushed to its limits, until little, if any, alpha is left.

You can also lever into beta funds (i.e. buy UPRO), but that has limits — because market return can be negative, you cannot re-lever into the fund infinitely; There is a chance that a large enough negative year will wipe you out, so your lenders will likely place very strict and very conservative limits to how much leverage you can apply. After all, even if your strategy blows up, they still want to be paid!

Quickly identifying alpha

To conclude, if you are looking at a strategy, and you’re trying to figure out if the strategy has alpha, a simple way to quickly estimate this is just to look at the strategy’s total return over a period which includes a number of high return years and negative return years.

If any of these are true, then there’s a good chance that the strategy has positive alpha:

- The strategy manages to return more than the market in all of those years.

- The strategy has a fairly stable, positive return in all of those years.

But if the strategy simply returns more in good years, but also loses more in bad years, then even if the strategy’s total return over all the years is greater than the market, the fund may not have alpha, or may even have negative alpha.

Footnotes

- A better and more complete definition can be found at https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/career-map/sell-side/capital-markets/alpha/. ↩︎

- You can’t compute this based on the data provided, but let’s go with it. ↩︎