Foreword

The SPX just had its worst week since 2020. You know, the year where everything shut down. Because of tariffs that everyone was warned about, for almost a year now. What happened?

As usual, a reminder that I am not a financial professional by training — I am a software engineer by training, and by trade. The following is based on my personal understanding, which is gained through self-study and working in finance for a few years.

If you find anything that you feel is incorrect, please feel free to leave a comment, and discuss your thoughts.

Boom! Tariff the World

After the market closed slightly up on Wednesday (4/2/2025), the president announced the actual tariffs that he and his team have been talking about for months (since before they were elected).

Despite having been forewarned about the tariffs for almost a year, the next day (4/3) markets dropped the most in percentage terms since the early days of 2020 around the start of the pandemic, and dropped even more the day after (4/4). Combined, this is the largest weekly percentage drop of the SPX since the chaos of early 2020, and the largest absolute 2 days points drop ever.

Tariffs He Wrote

Despite the tariffs being announced well ahead of time, it was still shocking because the administration had been touting a “reciprocal tariff”, but when the details were revealed, what actually happened was anything but.

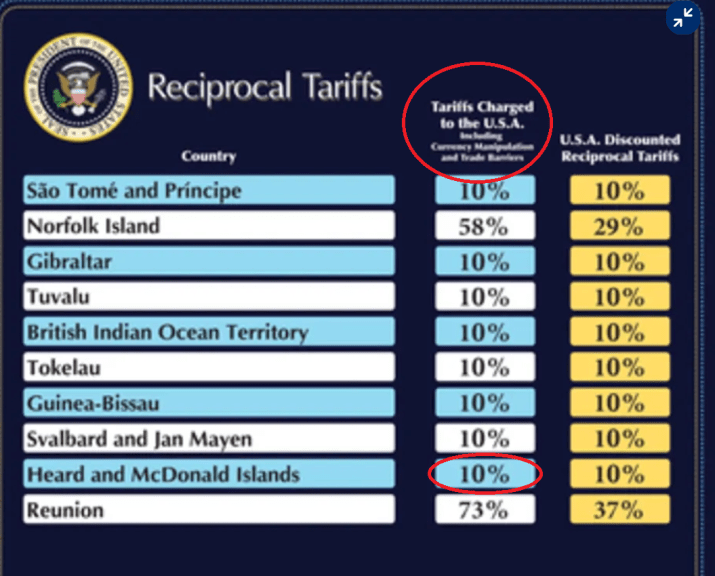

Reciprocal tariffs on most nations would amount to at most 10-20% for most items with a large number of items excluded. Instead, the administration went as far as to tariff effectively every nation by at least 10% for all imports, with some going as high as 50%. To justify the tariffs, the administration came up with what looks effectively like bogus tariffs the nations supposedly charge US exporters, even claiming that an uninhabited island populated mainly by penguins is charging tariffs on US exporters. I guess they don’t really like US fish?

After many commentors cried foul, the administration finally came clean and noted that the supposed tariffs imposed by other nations on US exporters is really just the ratio of US trade deficits to US imports from the country, with a 10% minimum cap.

To be absolutely clear, as many journalists, economists, financial advisors, finance professors and commentors have noted, this equation is utter bovine feces — despite dressing up the explanation with fancy maths symbols (that mean nothing!), the equation is meaningless in both economics and finance, an entire fabrication out of thin air.

Trade Deficits

In this one, incredibly unsophisticated, move, the administration has shown that it is deeply concerned about US trade deficits. So let’s talk about that for a while.

To simplify somewhat, a trade deficit is when a country (USA in this case) exports less to another nation than it imports from that nation. The deficit is simply the dollar amount of the difference between exports and imports to/from that nation.

As a general rule, deficits between 2 nations is a non-issue. Since trade is global and bilateral between different nation pairs, it is inevitable that there is an imbalance in trade between any 2 nations pair.

For example, Madagascar exports mainly vanilla beans to the USA, something that does not grow very well on American soil and climate, and so the USA has no real vanilla bean industry. However, because Madagascar is so poor, with the average person making just over $500 USD a year, there simply isn’t a lot that the average Madagascan can afford, and thus they simply don’t import a whole lot from developed nations which generally produce higher value added, and higher priced, goods — when you make $500 a year, an iPhone really isn’t something you think much about.

In theory, this trade deficit “goes away” when we consider the entire world. Let’s say the US imports a lot of Chinese stools, but exports a relatively smaller amount of tables to China — the US has a trade deficit with China. In the idealized Econs 101 case, this is fine because, in theory, the US will have a trade surplus (exports more to this country than the US imports from this country) with a 3rd country, say, Germany. Germany in turn has a trade surplus with China. So while every nation in our 3 nations scenario has a trade deficit with one nation, they also have a trade surplus with another, and the balance of trade (the sum of all trade deficits and surpluses for a single nation) will be 0, or at least very close to 0 over time, for all 3 nations.

In practice, this doesn’t really work. Empirically, we know that most developed nations have been consistently running balance of trade deficits for years, if not decades. There are many reasons for this phenomenon, but a large part of which is what the president said he is trying to address — unfair competition from some countries, such as China, where a combination of state level subsidies to domestic producers and tariffs or other barriers to foreign producers result in extremely one sided trade dynamics.

Face Off

But are trade deficits really bad? Think about it — some country is putting their citizens to work, and putting in their natural resources, to make a product that they then send to us. That country has spent non-trivial amounts of resources to produce that product, and in return, all they want from us is a few pieces of green paper. Green paper that we, as a country, can create almost for free.

In fact, Milton Friedman, a celebrated economist, made this point exactly.

Now, if you look at it from that perspective, it would seem that America should strive for larger trade deficits, not smaller!

Of course, reality is not quite so simple. There are very good reasons why a country would want to have a smaller balance of trade deficit:

- It is painful for those workers who are displaced by foreign goods. Yes, perhaps if you reduce the balance of trade deficit, you’ll incur a larger loss of jobs via not creating jobs in new industries that are never borne as the necessary inputs are never imported (as part of reducing your deficit). But as Milton Friedman notes (in the video above), those displaced are real people, with real voices, while those jobs that you never gain? They don’t exist yet, and thus have no say in the matter.

- If a country allows its industries to atrophy due to cheaper foreign imports, then at some point, expertise for producing those goods will be lost to that country. This means that any future goods based on that product may not be invented in that country simply because it doesn’t have that industry anymore. For example, a country is unlikely to invent the next generation of chips if they don’t even a chips industry.

- There are some products that a country needs in order to be independently strong. For example, steel is needed to build weaponry, and if a country imports all of its steel, then it is at the mercy of whoever sells it that steel — if they cut off supply, and then invades, the country will be in a pretty serious pickle.

- A large and prolonged balance of trade deficit is not sustainable. It may not be an issue in the near term, and problems may not emerge for many decades, but eventually, a country’s trade partners may find that they don’t really care for anything it produces, thus they have no need of its green pieces of paper, so they just cut it off from their goods. What then? Without industries, and without the expertise to restart those industries, the country would be at a dead end.

In summary, while deficits in the short term are good — they improve the average standard of living of the country’s inhabitants, in the long term, they can cause very serious issues for the country as a whole.

Sliding Doors

To be clear — I agree in general that a country needs to protect certain critical industries in order to remain independent and prosperous, and that tariffs are one of the tools to achieve those ends.

However, this needs to be better thought out and implemented. From inauguration day till just before the tariff details announcement on 4/2, the president made around 20 tariff announcements (in around 2 months!), most of which were changed or rescinded completely within days, if not hours. And then, out of nowhere, he announces tariffs that are wildly out of proportion to their stated intent, with what many speculators are saying seems like the output of a particularly bad LLM hallucination.

At the same time, the flipflopping of tariff policies resulted in serious business paralysis. Businesses typically order their inputs months in advance. If they cannot be sure what price they’ll ultimately pay for the inputs (since payment and tariffs both apply after the goods arrive), they simply cannot make any major decisions with regards to their supply chains and operations.

Finally, it is important to recognize that it takes years to build factories and to plan out supply chains. You simply cannot impose a tariff and demand companies shift their productions onshore in order to avoid the tariffs the next day. In the short run, there is nothing a company can do about their current supply chain, so they are forced to pay the tariff, even if they want to onshore their productions eventually.

If the short term goal of the tariffs are indeed to rebuild America’s industries, I’m all for it. But we have to recognize that rebuilding America’s industries is to serve a longer term goal, which is to strengthen the nation and enrich its people. Trying to rebuild industries by creating chaos in the business and international trading landscapes, while simultaneously alienating and insulting our allies is going to isolate America while making it that much harder to do business either domestically or internationally — the exact opposite of the end goal of a strong and prosperous nation.

Inflation

As discussed in Politinomics, tariffs are inflationary. There are some who argue against this, but I believe those arguments are wrong.

Some argue that tariffs are not inflationary because if the imported good becomes more expensive because of the tariff, consumers can simply substitute with domestic goods. This is a flawed argument, because it conflates inflation with inflation measures.

A similar argument is that as foreign goods become more expensive, it’ll trigger a recession, because consumers simply cannot afford to consume as much goods. As recessions are deflationary, the argument then concludes that tariffs are deflationary. Again, I believe this is a flawed argument, for the same reason:

As mentioned in Inflations, inflation measures are very flawed, though they are pretty much the best that we have right now. One pet peeve of mine about most inflation measures is that they usually take a basket of goods at some point in time, then measure the change in prices of those goods over some period of time to compute inflation rates. Most measures use baskets based on what consumers actually buy, which seems reasonable, except that it has a “too expensive” problem.

Imagine that you are currently able to afford to eat out every meal. However, for whatever reasons, restaurants all around the world suddenly raise their prices by 1,000%, though all other goods and services remain at the same prices. After the price hikes, you no longer are able to afford to eat out at all, so instead, you cook at home, which turns out to be cheaper than eating out before the price hikes, though it is not your preference.

In our scenario above, would you say that inflation is up, down or flat? Most people would say that inflation was up, despite the fact that you are now spending less money cooking at home. However, most inflation measures that use the “basket of goods consumers buy” approach will initially register a spike in inflation (due to the 10x increase in eating out costs), until the basket of goods is updated to reflect that you no longer eat out, at which point it’ll register deflation, because now you are spending less money on your basket of goods.

Obviously, this is wrong — inflation clearly went up, the fact that you are no longer able to afford your previous lifestyle is testimony to that.

Finally, the last argument I’ve heard is that tariffs are paid for by the exporters, and that somehow, tariffs are a tax on the exporters and so consumers will not see price hikes. Empirically, this is wrong — multiple goods are forecasted to go up in prices, and multiple companies have stated that they plan to hike prices in response to the tariffs.

The key to remember is this — businesses are commercial ventures, they need to make a profit to survive. There is no business in the world that can survive losing money perpetually (companies that do that are called charities, not businesses, and they are funded by donations).

Now, some may claim that businesses are making so much money, they can afford to make a little less. That argument may sound correct, right up till you look at the details. Most businesses (outside of tech and finance) make profit margins of around 5-15%. Retail businesses, in particular, are famous for having razor thin margins, some as low as 1-3%. What do you think happens if you are making 10% margins, and then a minimum 10% tariff is imposed on the inputs into your businesses? 10 – 10 = 0.

Immediately after the tariffs are imposed, some businesses may be able to raise prices, while others may not raise prices for a while. For example, companies which sell mostly online tend to be able to adjust prices faster, while brick and mortar stores tend to lag because their prices are on physical price tags and it takes a while to manually adjust all the price tags. Similarly, businesses locked into long term purchase orders may not be able to raise prices due to contractual obligations.

However, in the long run, where short run considerations like price tags and time limited contracts are no longer factors, the business can, and literally must (in order to stay alive), raise their prices. These raises may be gradual or fast, depending on the industry, and they may be explicit (prices actually going up) or implicit (reduction in costs due to better productivity not being passed on to customers as price decreases). But one way or another, the business must raise its prices due to the tariffs, or they simply go bankrupt.

Possibilities

So what are the possible outcomes of these tariffs? First, I must say that I am extremely unqualified to discuss this — I have no inside knowledge of how the administration thinks, and obviously I cannot see the future. Also, all of these are extremes — I don’t think any of them will become reality in their entirety, but instead, the final outcome may incorporate aspects of each of these.

Tariff gotcha

Possibly the best possible outcome for America. The president uses the tariffs for bargaining leverage to negotiate better trading terms with the rest of the world, and the tariffs are never actually implemented, or they are only live for a very short (days) period of time.

Soon after the announcements of the tariffs, Vietnam is already in talks with the president to reduce their duties on US goods.

Oh, never mind

The president, willingly or forced, retracts the tariffs without getting a deal with the rest of the world, before tariffs actually go live, or go live for only a very short (days) period of time.

Tariffs are, legally, a tax, and the Constitution endows only Congress with the power to impose new taxes or update existing ones. However, Congress has passed laws in the past which allowed the president to unilaterally impose or adjust tariffs in certain circumstances. It is possible that Congress changes its mind and removes the president’s authority to impose/update tariffs.

Fight club

The tariffed countries retaliate by imposing their own tariffs or other trade barriers, effectively engaging the trade war head on. The fight may spiral with each side escalating back and forth until one side surrenders, or some compromise is reached.

This would be seriously detrimental to the economies of both the US and the countries involved (assuming both sides are a large percentage of trade of the other). There is no winner in this situation, only a loser and a slightly less battled loser.

In particular, the tariffs currently slated to be implemented are already so high for some countries that they are effectively already cut off from the US market. This means that for them, higher US tariffs would make very little meaningful difference, so they may be more inclined to fight.

Given that many goods imported into the US have no other source of readily available producers, this would mean that US consumers will simply be deprived of those goods until new production can be started up somewhere else (or in the US itself), which can take years/decades, depending on the goods.

China has already announced actually reciprocal tariffs on the USA.

New BFFs

The worst possible outcome for the USA, would be if some of America’s largest trading partners decide to cooperate and defend against the new tariffs as a bloc. The new bloc could be used to gain leverage over the US to extract better trading terms, possibly even worse (for the US) terms than existing ones, or, much worse yet, the bloc could effectively trade amongst themselves, cutting out the US entirely.

Canada sent trade envoys to the EU soon after their recent elections (before tariff details were revealed), and rumors are that they are thinking of forming a bloc to better negotiate with the US, or perhaps even to cut out the US entirely.

Fin

Nobody really knows how this will all end. While some countries have stated that they will not contest the tariffs but will instead work towards a compromise, they may change their minds if other countries start getting preferential treatment. At the same time, countries that opted to fight may find the president to be unyielding, and quickly lose their appetite to continue the war.

In the end, this entire mess creates chaos in international trading, a lifeblood of effectively all large businesses and many/most small/medium ones as well. It is no wonder that the markets are treating this as a very serious event, on par with the pandemic.

For now, all we can do is watch helplessly as the leaders of the world try and secure what’s best for their nations, praying that whatever happens won’t be too detrimental for us, personally.

Are you not liberated?