Foreword

QE, money printing, fiscal stimulus… inflation?! What is inflation? What determines how high inflation gets?

This is a discussion of my personal model of inflation and how it occurs.

I want to be absolutely clear here — this is based entirely on personal study and understanding — I am not a trained economist. All I have, is a high school diploma(1) in Economics, from over 2 decades ago — no doubt there are gaps and/or flaws in my understanding.

If you find anything that you feel is incorrect, please feel free to leave a comment, and discuss your thoughts.

What is inflation?

First off, let’s define inflation. The official economics definition of inflation has undergone some changes throughout history. In this post, I’ll be using the more common, modern day textbook definition which is roughly: Inflation is the general increase in prices of goods and services, and thus a general decrease in the purchasing value of money.

In the quantity theory of money, the equation of exchange gives us(2):

MV = PT

(Simplified) Equation of exchange, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equation_of_exchange

where

- M – The total nominal money supply

- V – The velocity of money

- P – Price level

- T – The number of financial transactions

So, assuming the number of financial transactions is the same, then an increase in P (inflation) is simply an increase in MV.

i.e.: Inflation is a product of increasing total money supply times the velocity of money.

Of particular note, and this is something that a lot of people get wrong — inflation is the increase in general price levels:

- Inflation is not the increase in price(s) of one or even a handful of products.

- It needs to be an increase in prices of all or almost all products.

- Inflation is not high prices.

- Inflation is the increase in prices.

- Even if prices are still low after the increase, it is still inflation.

- Conversely, if prices are high, but didn’t increase, then it is not inflation.

- If after a round of high inflation (large increases in prices), prices remain stable at very high levels, then inflation did not persist.

- Just because the effects of inflation are permanent, need not mean that inflation itself is permanent.

- For prices to go back to “normal” levels, would require negative inflation (decrease in prices), also known as deflation.

Hyperinflation

In today’s financial environment, whenever inflation is brought up, people immediately jump to hyperinflation, conjuring up images in their minds of stacks of useless cash pushed around in wheelbarrows.

To be clear, the official definition of hyperinflation is 50% month over month increases in prices, which translates to around 129x (12974.63%) annually. Compared to that, the current 5-6% annual inflation rate is pretty tame.

That said, what causes hyperinflation? Well, happily(3), history provides a lot of examples of where hyperinflation struck. In the popular retellings of these events, the story generally goes along the lines of, “the government/central bank printed more and more bank notes, resulting in an excessive supply of these notes, which then resulted in their devaluation and thus inflation”.

In my opinion, that is a very misleading description of what transpired. As a thought experiment, imagine if the governments of the hyperinflationary events were to print the bank notes, and then burn them up in a giant bonfire. Do you think there would have been hyperinflation, or even high inflation then? It seems to me, that the excessive printing of money was a necessary, but not sufficient step towards hyperinflation. It was the left out bit, the part where “the government then spent the newly printed money with abandon”, which resulted in hyperinflation. In effect — simply printing the bank notes did nothing. But distributing them via government spending (i.e.: fiscal policy), resulted in the increase of money supply(4) (increase in M), and the excessive spending by the government resulted in more money being spent and circulated (increases in V). And that excessive spending is the actual trigger of hyperinflation.

In simple terms, it is not “printing money” that is the problem, but the attempt at creating “value” out of thin air — by printing bank notes not backed or offset by anything, and then spending them as if they were valuable.

Monetary vs fiscal policy

Just a quick note here, because we are going to talk about monetary and fiscal policies a lot.

Monetary policies are generally policies with regards to the money supply .

Fiscal policies are generally policies with regards to taxation and government spending.

In modern society/finance, you can think of monetary polices loosely as “what central banks decide to do”, and you can think of fiscal policies loosely as “what governments decide to tax and spend on”.

Quantitative easing

Since 2009 when quantitative easing (QE) started in the USA (and most of the world), there have been many analysts going on about how QE is printing money, and that it would result in hyperinflation. These doomsayers make very compelling arguments by equating QE to money printing, conjuring up images of massive industrial printers working overtime. However, it has been over 12 years, and only fairly recently did inflation even get comfortably past the 2% that central banks generally target. What happened?

Facts

Before we discuss what happened with QE, let’s talk about some facts:

- In the USA, QE started in 2009, and was increase multiple times since then, with the latest increase in around March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

- In the USA, inflation from 2009 to March 2020 has generally been low to very low, generally in the 0-2% range.

- Most other developed nations saw similar trajectories with regards to QE and inflation as the USA, though numbers and dates may be slightly different.

- Japan started aggressive monetary policies in the early 90’s, culminating in QE around 2001 — 8 years before most of the other developed nations.

- Japan’s annual inflation rate up to March 2020 has generally been extremely low, with bouts of deflation (negative inflation).

- In March 2020, in addition to aggressive monetary policies by central banks around the world, fiscal policies around the world also stepped up, culminating in a series of transfer payments(5) around late 2020 into early 2021.

- In March 2021, we finally saw inflation pick up in the USA.

- Again, most of the world mirrored the USA’s experience since 2020.

Printing money

The first thing to note when discussing QE, is that it isn’t really “printing money”. In the popular nomenclature, “printing money” generally implies a(n) (attempted) creation of additional “value” out of thin air. However, that is simply not what QE does.

Imagine if you are a bank and I am a client. I choose to deposit $1000 cash with you. In exchange for my cash, you give me a little deposit slip saying I now have $1000 with you. Now, I can write a check against my $1000 with you, and most places would accept my check as payment for services. In effect, that check is “money”(6), and I have, almost literally, “printed money” (with a pen!). I’m sure we can all agree, that lil’ ol’ me isn’t going to cause inflation, much less hyperinflation.

In technical terms, when I deposit $1000 with you, you created 2 entries in your ledger — one under “assets”, which is the actual $1000 cash I deposited with you. The other entry is under “liabilities”, which is the $1000 you now owe me. The total amount of “value” in the system is the same — the $1000 under your assets cancels out the -$1000 under your liabilities.

In a similar fashion, central banks are the banks of normal banks — normal banks can deposit their money with central banks. Generally, (normal) banks need to put up a certain amount of money with their central banks known as reserves. There are complicated rules around the minimum level of reserves a bank needs, and we won’t go into that here, but basically, for a bank to operate, it needs a certain amount of money in the central bank. Any money the bank has in excess of that reserve requirement, is called “excess reserves”(7).

During the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, a lot of assets held on banks’ balance sheets were deemed “risky”. To avoid bank failures, regulators demand that banks increase their amount of reserves. However, there was a general liquidity crunch at the time, so banks couldn’t really do that. At the time, central banks stepped in, and essentially bought up a lot of these assets on the banks’ balance sheets (generally government debt, and government guaranteed mortgage debts). In some sense, this is the same as me depositing my $1000 with you — the banks give the Federal Reserve assets worth $X(8), and the Federal Reserve give the banks a little deposit slip saying “I now owe you $X” (9). On the Federal Reserve’s books, under “assets”, we have these newly bought assets, and under “liabilities”, we have $X owed to the banks.

As you can see, there isn’t really any attempt to create “value” out of thin air. Yes, in a very literal sense, “money is printed” (via increase in reserves on the banks’ books). But that “money” is really just a matched asset/liability pair on the Federal Reserve’s books, and the net “value” in the system is the same — just as me depositing $1000 with you, and then spending that $1000 via a check doesn’t really create “value”.

Liquidity

After the Great Financial Crisis, central banks continued QE, essentially buying up assets from banks, and increasing banks’ excess reserves account (after the immediate crisis, banks already meet your reserve requirements, so any excess sales of assets to central banks really only increase excess reserves).

A further charge of the doomsayers, is that these excess reserves is money, and thus this “money printing” causes inflation.

As we’ve discussed above, while this is “money printing” in the literal sense, there is no attempt at creating “value” out of thin air unlike hyperinflationary episodes from history, because while the central banks issue (excess) reserves, they also take away “value” by taking away equivalent value in assets.

However, there are some effects of this QE! By buying up assets in a price insensitive manner, the central banks effectively put a floor on the value of some assets (generally safe assets like government bonds and government backed debts). This has 2 effects:

- These assets that the central banks target effectively have a higher clearing price (i.e.: become more expensive than they would be without QE).

- The money that was previously invested in these assets now need to be invested elsewhere.

Together, this resulted in what is colloquially known as “yield tourism” — investors forced out of safe Treasuries and government backed debts, now have to “reach for yield” by buying more risky assets, such as corporate debt, municipal bonds, equities, etc.

In effect, this increased the liquidity in the system, by both reducing the amount of assets that money can buy, and increasing the amount of money in the system. However, this effect is generally confined to financial markets — the Federal Reserve really isn’t in the market to buy baby diapers or new cars. The money displaced by the Federal Reserve’s buying will generally go into buying other financial assets instead of being spent on consumer goods.

In simple terms, if you’ve $1000 to invest, just because the Federal Reserve prevents you from buying some financial assets, doesn’t mean that you’ll just spend that $1000 on chocolate bars! You will likely just invest in something else — that $1000 doesn’t really make it into the consumer goods market.

Putting it all together

In summary, I believe that QE does not result in inflation. Instead, it results in “financial assets inflation”, which is colloquially used to mean increase in financial asset prices only. This is also why, I believe, the prices of stocks, bonds and various other liquid financial assets have been going up non-stop since 2009.

How then, do we explain the high inflation that started around March 2021? Well, recall under “Facts” above, that QE wasn’t the only thing that happened in 2020. Something else happened. Something new. Something changed in mid/late 2020 — governments started massive fiscal policy programs.

Recall from our short note in “Hyperinflation”(10) how inflation doesn’t really begin until that newly created money is spent. Well, that newly created money started being distributed for spending around mid/late 2020 into early 2021. And then we saw inflation take off in early 2021.

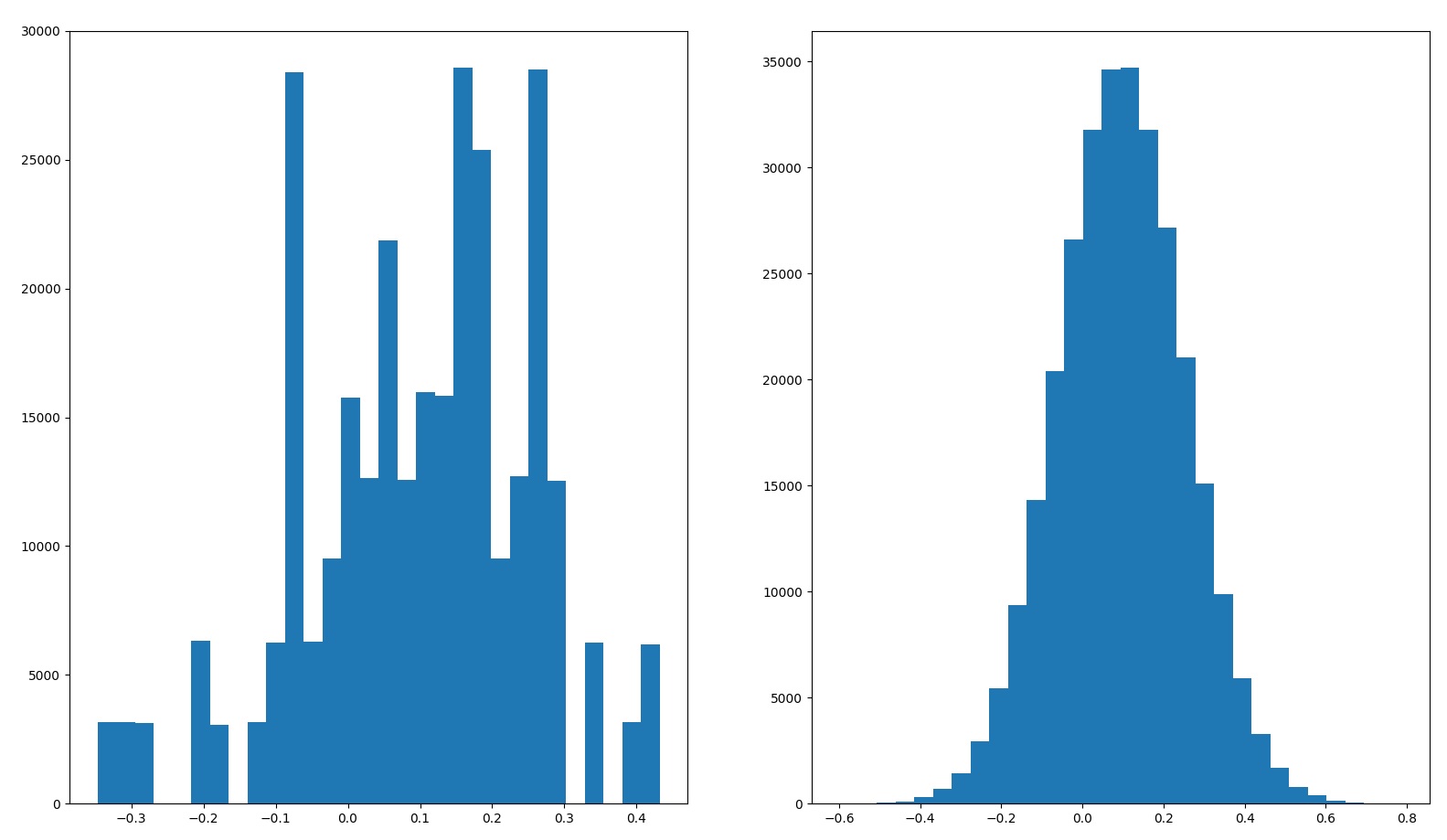

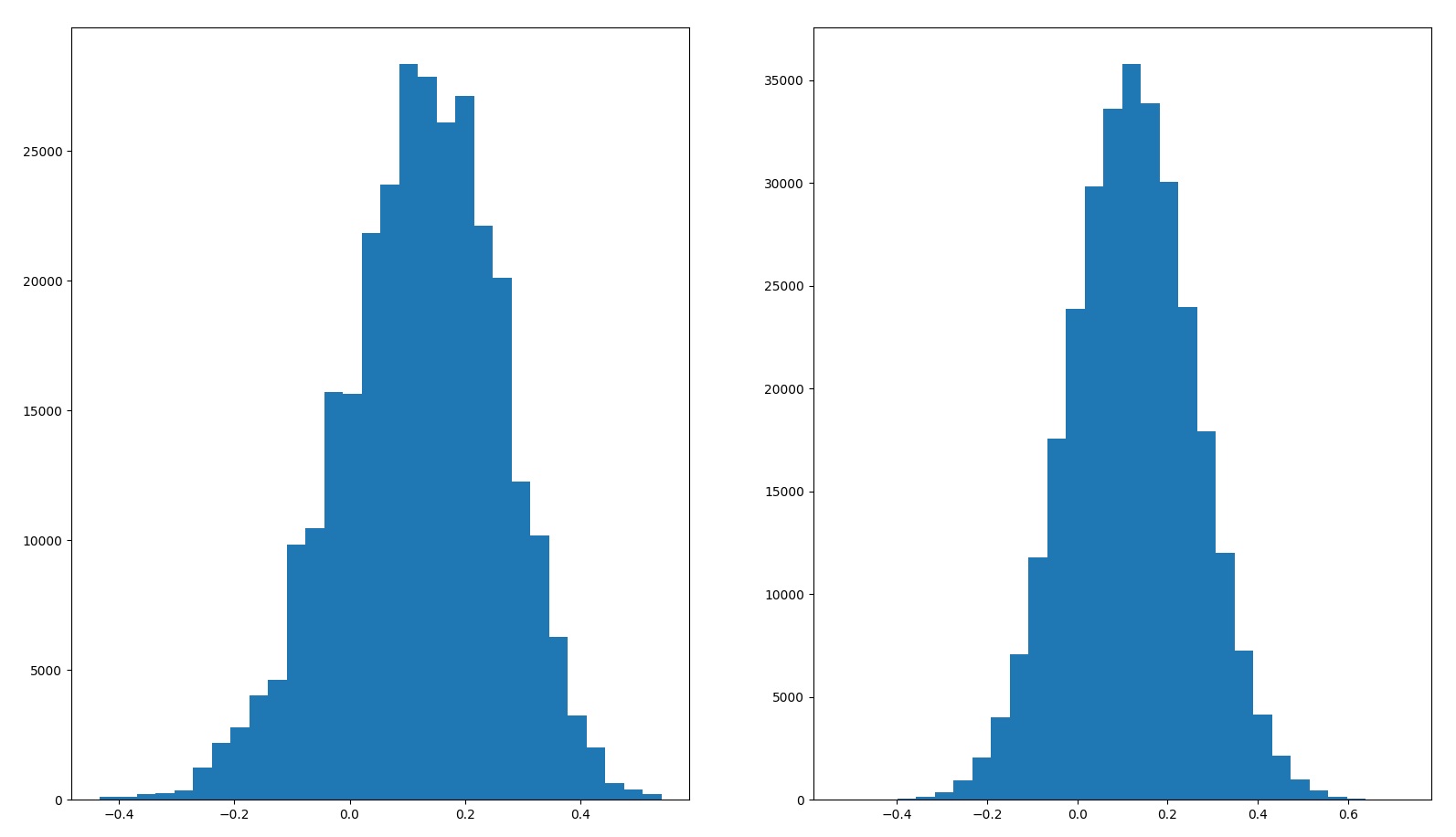

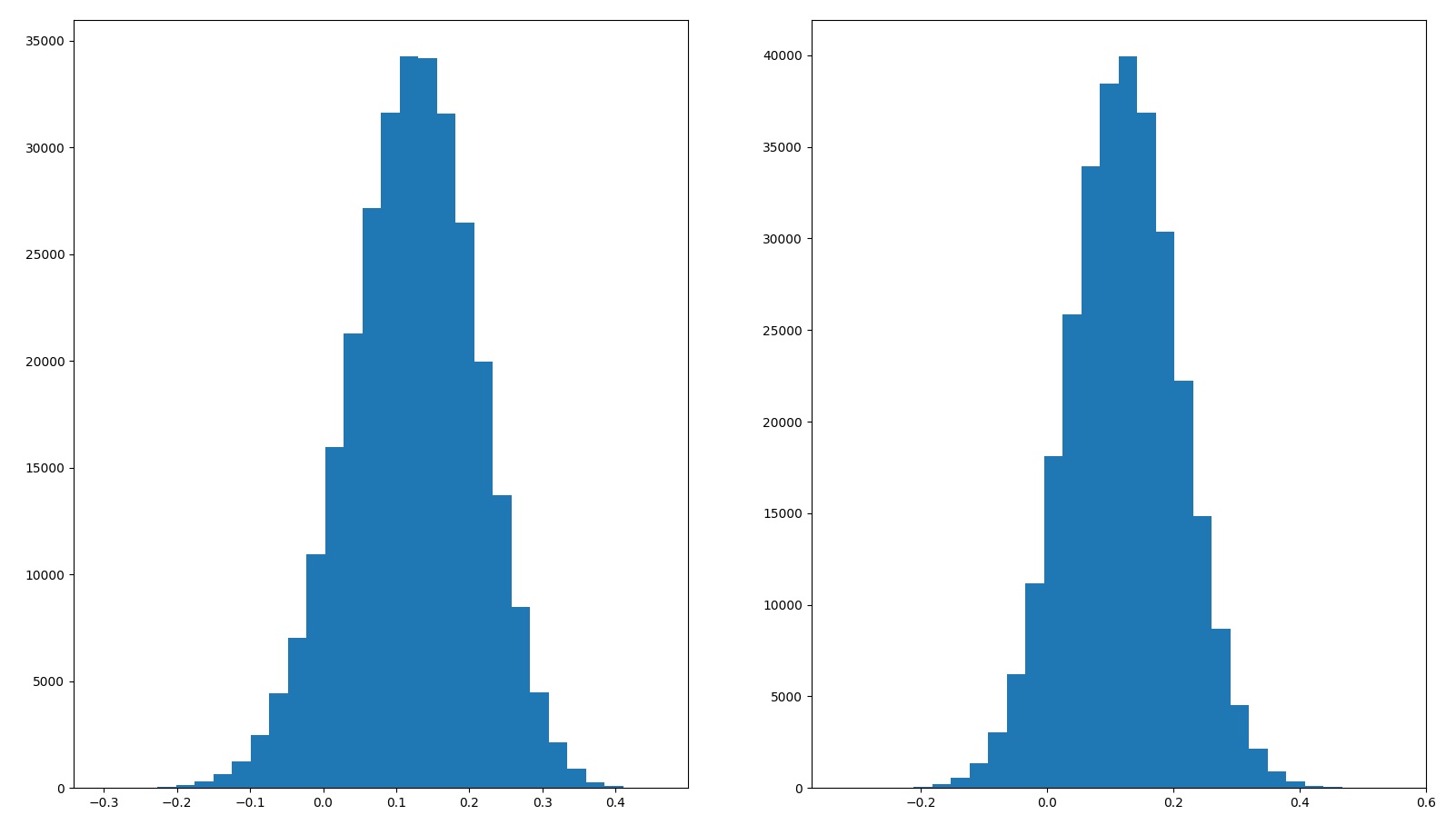

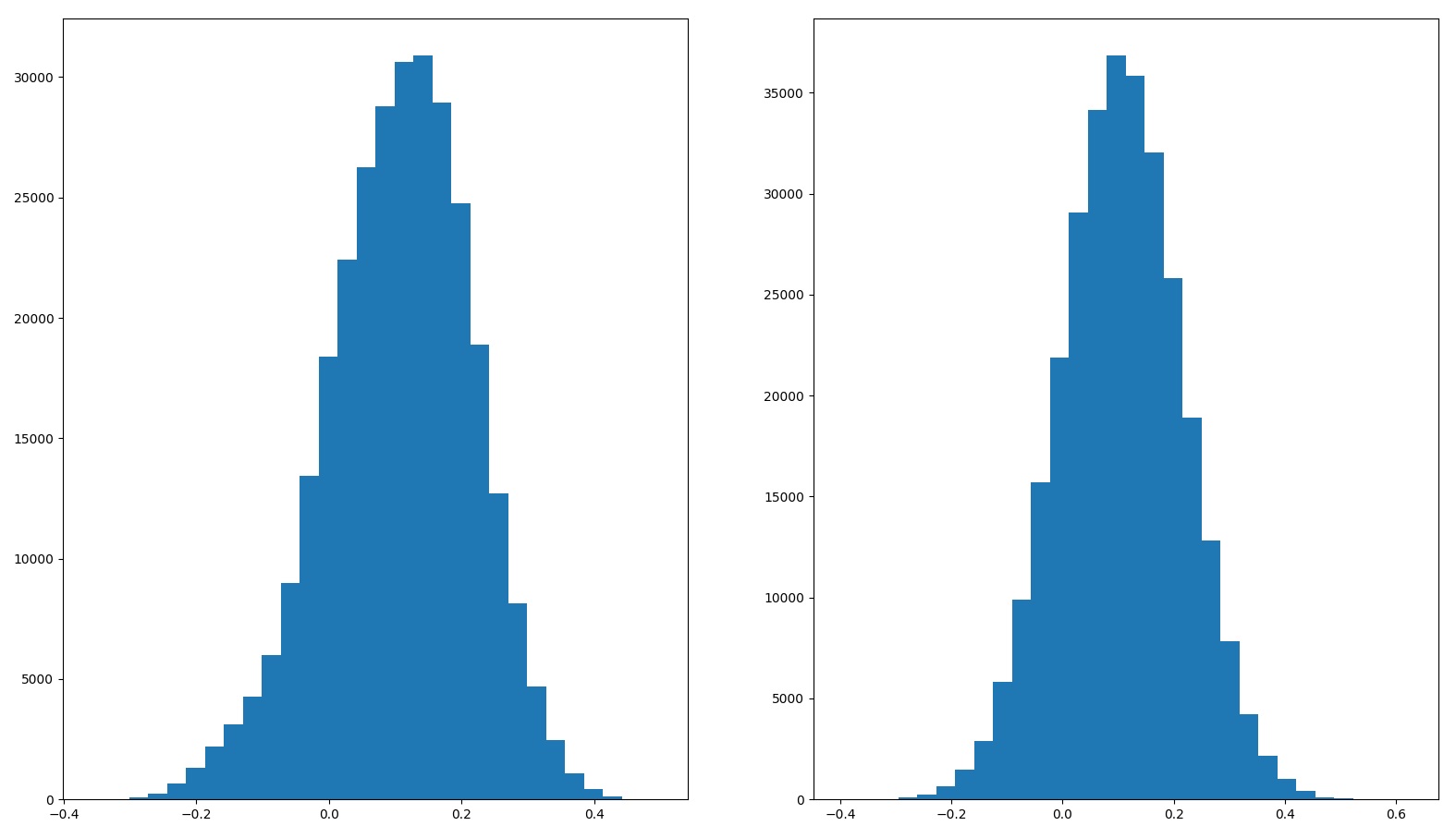

In technical terms, before 2020, while M (the money supply) was rapidly increasing, V (the velocity of money) was rapidly decreasing. As a result, the product MV was actually increasing at a rather slow rate, thus low inflation. After late 2020, the rate at which V decreased slowed down dramatically (it is now almost flat), but M increased dramatically. As a result, MV started increasing at a higher rate, i.e.: higher inflation.

Crimping inflation

Recall that in my August inflation update I noted that I believe the Federal Reserve has all the tools it needs to combat inflation. How would that work if I’m now saying fiscal policy is the cause of inflation?

Well, one way of analogizing about this is that loose monetary policy is fuel, and loose fiscal policy is heat. You cannot start a fire with only fuel, and you cannot start a fire with only heat. You need to combine both(11) to start a fire.

Which is to say, I believe that the Federal Reserve can clamp down on inflation by simply tightening monetary policies — inflation can be reduced by simply reducing money supply faster than the velocity of money. And since the velocity of money isn’t really going up — it’s just “mostly flat” (compared to rapidly decreasing in the past ~2 decades) — the Federal Reserve can simply cool down inflation by stopping QE and increasing interest rates back to “normal”. If need be, they can even increase interest rates to high levels, like what Volcker did in the 70’s (12).