Foreword

This is a quick note, which tends to be just off the cuff thoughts/ideas that look at current market situations, and to try to encourage some discussions.

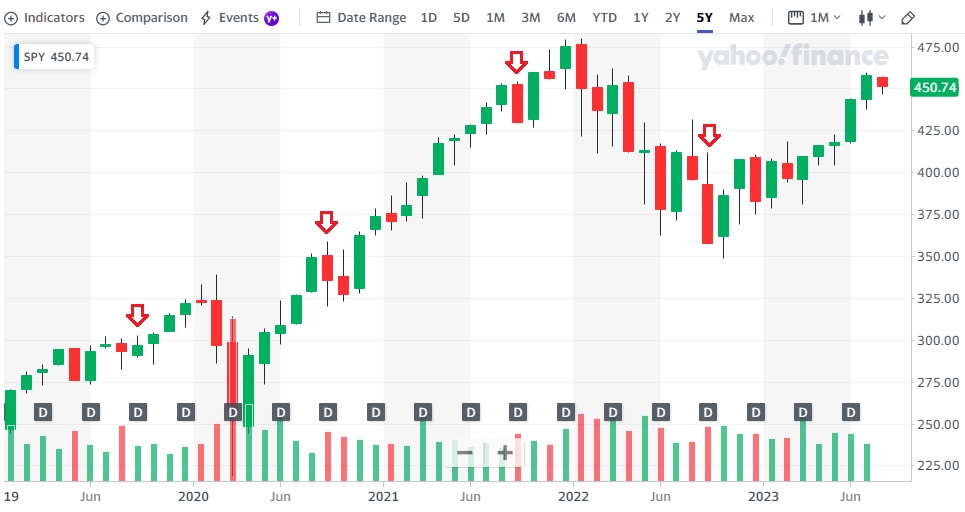

The end of the year is upon us, and as with most years, it appears that the Santa Rally is upon us.

As usual, a reminder that I am not a financial professional by training — I am a software engineer by training, and by trade. The following is based on my personal understanding, which is gained through self-study and working in finance for a few years.

If you find anything that you feel is incorrect, please feel free to leave a comment, and discuss your thoughts.

Update

Continuing with our short term trading updates:

If you follow me on StockClubs (1), you may notice that after the Treasury’s Quarterly Refunding Announcement (QRA), followed by the rather dovish FOMC meeting, I’ve closed my market shorts. Across all my accounts with a similar short, the losses and gains net out to a small gain.

At the same time, I had on a bunch of quarterly earnings reports plays, mostly doing with shorting tech names. While the majority of calls were wrong (TSLA – went down after earnings [right], NFLX – went up , GOOG – went down, MSFT – went up, SNAP – went up, META – went down, AMZN – went up, INTC- went up), the play was that given how markets were punishing weak and even decent earnings while not really rewarding beats, the overall risk/reward for shorting into earnings seemed good.

And I would have made a small profit too… if I hadn’t been too greedy. On the day of META’s earnings, the market went down just after I opened the short, giving me a small gain even before the earnings report. If I had left the trade on, or taken profit, I’d have a net gain (across all the trades). Instead, I closed the position, and reopened a put spread further out, while opening a call spread — the bet was that given the already downbeat market, META will likely move regardless of earnings, though it now had a higher chance of going up.

Well, META moved down the next day, and I was sitting on pretty decent gains on the new put spread — more than enough to cover the costs of the call spread… except that I got greedy and I decided to let it sit to capture more profits. Of course, that evening AMZN reported stellar earnings, so good in fact, that it caused the entire tech sector to rally, and my META short gains to vaporize.

So now my earnings report play is sitting on a bunch of losses, large enough that across both market and earnings plays, I’m down slightly. Bummer.

Santa Rally

Prior to the Treasury QRA, I was thinking that there’s a 50/50 chance of a Santa Rally this year — there are a lot of risks in the world:

- Potential of middle east regional war leading to oil price spike

- American consumer looks increasingly tapped out

- China financial weakness

- Potential Japanese tightening due to inflation

- Potential US government shutdown in mid November

- Credit losses on commercial real estate properties

- Housing market turning weaker

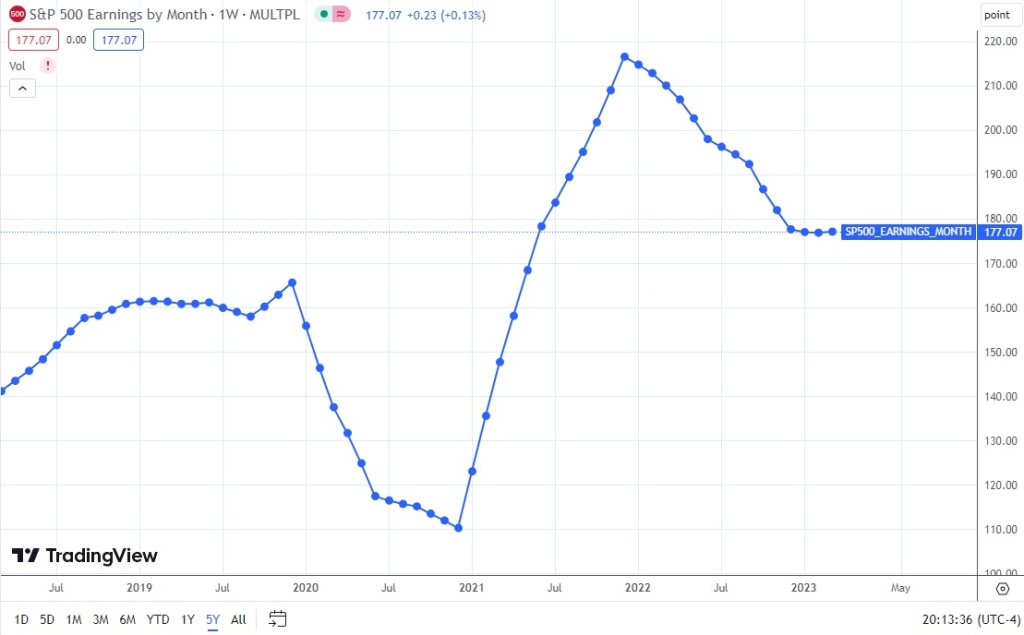

- Earnings from companies seemed weak

But there are also a lot of potential catalysts for a rally:

- Israel seems to be moderating their stance somewhat after international pressure

- American consumer is still much stronger than expected

- China seems to be starting to ease

- Ueda seems to be going about Japanese tightening very timidly

- US House of Representatives elected a speaker who seems to be keen to avoid a shutdown

- Losses on commercial real estate seems confined to commercial real estate, mostly office spaces

- Housing market weakness seems mostly limited to certain regions

- Earnings season is mostly done, at least for the big names.

So I was on the fence about holding my shorts, closing them or even opening longs.

But the Treasury QRA and the following Fed FOMC press conference suggested two things:

- Both the Treasury and the Fed seemed keen to avoid pushing the market too hard, and seemed in fact to be trying to limit longer duration Treasury bond weakness

- Future rate hikes seemed unlikely unless something dramatic changes

Given that both monetary and fiscal policies appear to be trying to keep markets happy, as long as nothing dramatic happens, it feels like on the net, betting on a Santa Rally seems like a better risk/reward play till the end of the year.

In that spirit, I’ve closed all my market shorts across all accounts. There are also no earnings report that I am really excited to play for the rest of this earnings season. Instead, I’ve opened a few bullish positions across my accounts:

- Call spreads on TLT

- Call spreads on QQQ

- Call spreads on VOO

The reason why I’m switching from betting on SPY is because of wash sales rules — I avoid trading the same names across the December/January divide, as that makes taxes regarding wash sales easier to deal with (you don’t have to carry losses into the new year). By only trading QQQ now, I can just avoid QQQ in January and only trade SPY then.

Hope and a prayer

Readers should be reminded that my previous short plays did not quite pan out as expected, so there’s a very good chance that this new long play will be rewarded with a lump of coal.

I guess we’ll see….

Footnotes

- Disclaimer: I am an investor in StockClubs, and only one (out of 10+) of my brokerage accounts are shown there.